Why Triptans Work When Serotonin Fails: A Conflict backed by Magnesium-Driven Model of Migraine.

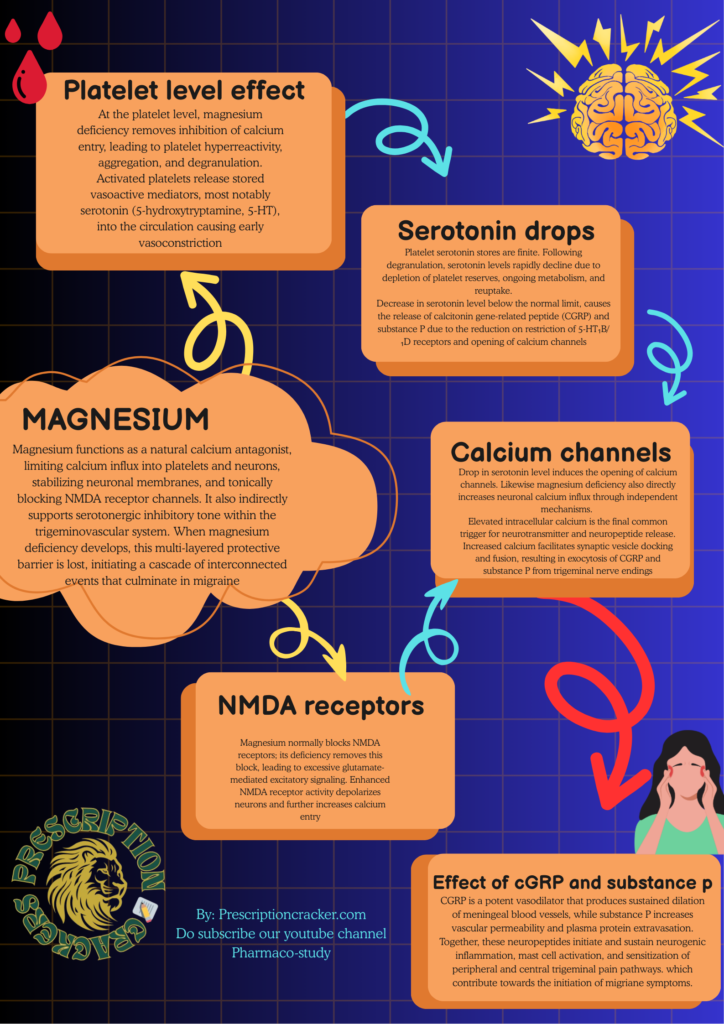

Magnesium is a critical homeostatic ion that maintains vascular, platelet, and neuronal stability. Under physiological conditions, magnesium functions as a natural calcium antagonist, limiting calcium influx into platelets and neurons, stabilizing neuronal membranes, and tonically blocking NMDA receptor channels. It also indirectly supports serotonergic inhibitory tone within the trigeminovascular system. When magnesium deficiency develops, this multi-layered protective barrier is lost, initiating a cascade of interconnected events that culminate in migraine.

Effect of Magnesium Deficiency on platelets:

At the platelet level, magnesium deficiency removes inhibition of calcium entry, leading to platelet hyperreactivity, aggregation, and degranulation. Activated platelets release stored vasoactive mediators, most notably serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), into the circulation. This serotonin release is abrupt, unregulated, and occurs primarily within the vascular compartment. Circulating serotonin preferentially activates vascular 5-HT₂ receptors (though also possesses inhibitory effect on 5-HT₁B and 5-HT₁D receptors), which are readily accessible from the bloodstream, producing transient vasoconstriction of cerebral and meningeal vessels. This early vasoconstrictive phase corresponds clinically to prodromal migraine features.

However, platelet serotonin stores are finite. Following degranulation, serotonin levels rapidly decline due to depletion of platelet reserves, ongoing metabolism, and reuptake. Thus, migraine physiology is marked not by sustained serotonin elevation, but by a sharp rise followed by a pronounced fall in serotonin availability. This decline in serotonin represents a pivotal transition point in migraine pathogenesis.

Working of Serotonin:

Under normal conditions, a steady background level of serotonin is present around the trigeminal nerves that supply the meninges (the coverings of the brain). This serotonin is not meant to trigger pain or pleasure here; instead, it acts quietly in the background to keep these nerves calm and under control.

Serotonin does this by attaching to special receptors called 5-HT₁B and 5-HT₁D receptors, which sit on the endings of trigeminal sensory nerve fibers. These nerve endings are the same ones that release pain-producing chemicals during a migraine. When serotonin binds to these receptors, it sends a “slow down” signal into the nerve.

Inside the nerve cell, this signal switches off pathways that normally make the neuron excitable. It lowers the level of chemical messengers that promote firing, reduces the entry of calcium into the nerve ending, and blocks the machinery that releases stored neurotransmitters. In simple terms, the nerve becomes less jumpy and less likely to fire.

Because calcium entry is reduced, the nerve cannot easily release pain-related substances like CGRP and substance P. These substances are powerful migraine triggers because they dilate blood vessels, inflame surrounding tissues, and amplify pain signals. By preventing their release, serotonin keeps the trigeminal system quiet and helps stop migraine attacks from starting.

So, under healthy conditions, serotonin acts like a protective gatekeeper. It doesn’t eliminate pain completely, but it sets a threshold that prevents harmless stimuli from turning into a full migraine. When serotonin levels drop or its signaling is impaired—as happens in menstrual migraine or magnesium deficiency—this inhibitory brake is lost, and the trigeminal nerves can easily become overactive, leading to CGRP release and migraine pain.

Effect of magnesium deficiency on NMDA receptors and Calcium Channels:

Magnesium deficiency directly increases neuronal calcium influx through independent mechanisms. Magnesium normally blocks NMDA receptors; its deficiency removes this block, leading to excessive glutamate-mediated excitatory signaling. Enhanced NMDA receptor activity depolarizes neurons and further increases calcium entry. In addition, magnesium deficiency reduces the threshold for activation of voltage-gated calcium channels, amplifying calcium influx during action potentials. Thus, magnesium deficiency promotes neuronal calcium overload through both direct ionic effects and indirect loss of inhibitory serotonergic control.

Elevated intracellular calcium is the final common trigger for neurotransmitter and neuropeptide release. Increased calcium facilitates synaptic vesicle docking and fusion, resulting in exocytosis of CGRP and substance P from trigeminal nerve endings. CGRP is a potent vasodilator that produces sustained dilation of meningeal blood vessels, while substance P increases vascular permeability and plasma protein extravasation. Together, these neuropeptides initiate and sustain neurogenic inflammation, mast cell activation, and sensitization of peripheral and central trigeminal pain pathways.

Clinically, this stage corresponds to the pain phase of migraine, characterized by throbbing headache, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and central sensitization. By this time, serotonin levels are already low, explaining why vasodilation and inflammation dominate rather than vasoconstriction. CGRP becomes the principal driver of migraine pain and associated symptoms.

Triptans therapy:

This integrated cascade also explains the apparent paradox between endogenous serotonin and triptan therapy. Platelet-derived serotonin released during magnesium deficiency is non-selective, short-lived, and largely confined to vascular receptors, failing to provide sustained inhibitory control over trigeminal neurons. In contrast, triptans such as sumatriptan are selective 5-HT₁B/₁D receptor agonists that directly restore inhibitory restraint at trigeminal nerve terminals. By re-inhibiting calcium channels and suppressing CGRP and substance P release, triptans abort migraine attacks despite low endogenous serotonin levels.

In summary, magnesium deficiency initiates migraine by removing platelet and neuronal calcium regulation, triggering platelet aggregation and serotonin release followed by serotonin depletion, abolishing serotonergic inhibitory restraint on trigeminal neurons, enhancing glutamate-NMDA excitotoxicity, and directly increasing neuronal calcium influx. These converging mechanisms culminate in excessive CGRP and substance P release, producing neurogenic inflammation, vasodilation, and migraine pain. This unified model explains why magnesium supplementation is effective in migraine prevention, while triptans are effective in acute migraine termination.

Pharma Bulletin, Research Articles & Case Studies

Disclaimer

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It does not substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before starting any medication.